Collecting Sap and Making Syrup from Walnut Trees

Louis Saur, fourth generation farm co-owner, loved the Eastern BlackWalnut--a tree both valued for its dense, dark, straight-grained wood and cursed for its ankle-twisting green-husked nuts. Much in the way Benjamin Franklin believed the turkey to be the quintessential American bird, Louis considered the Eastern Black Walnut to be the quintessential American tree. So, he would walk around the property, pressing any walnut he came upon deep into the soil with the heel of his work boot.

And that is why, Carriage House Farm's pasture and wooded spaces are lousy with Black walnuts to this day.

What Louis may not have known about his favorite nut-producing tree is that it is also a source of high-sugar sap that can be turned into syrup just as readily as sap from sugar maples. Black walnut syrup is, in fact, very similar to maple syrup with the addition of notes of nuttiness and bitterness for a slightly more complex flavor.

One year, while we were researching a better method to collect, hull, cure, and crack black walnuts, we found the first research and articles about less-commonly known sap-producing trees as alternatives to sugar maples. It was valuable research for regions without sugar maples or suffering from a general warming trend that was shortening harvest seasons for maple syrup. And the research was a boon to us--giving us a new experiment to try on the farm with all of our many black walnut trees..

Research like Cornell University's small farm research programs paper on harvesting black walnut sap or articles in fringe lifestyle magazines and blogs like Wildfoodism's article on 22 Trees That Can Be Tapped For Syrup began popping up on the internet and discussed at farm conferences. After doing some reading and tinkering we began experimenting in 2016 and are now on our third season of harvest. Having never harvested maple sap or reduced sap to a syrup, there was a double-edged learning curve to overcome. In addition to the black walnut sap, we were harvesting from silver and green Maples, which produce a sap similar to Sugar maples but without as high a sugar content.

We have not fully perfected our harvest or production, and so we don't yet have syrup to bring to market. We do hope to in the next year or two. In the meantime, we love to be able to share stories about what we're working on and how past generations' farm interests sometimes unpredictably dovetail with the interests of the present day and future owners. Such is the occasional magic of the small family farm.

If you're curious about the more nuts-and-bolts, technical details of what we have discovered in our tinkering, please read on. And if you have any questions, please leave them in the comments!

So, this is our experience after three years of experimentation:

Tree Species Tapped: The Eastern Black Walnut, Juglans nigra

Growth Region: Zone 6A in the Central Ohio River Valley that contains a large number of micro-climates. The property is a mixed location with some trees being a high water table flood plain/river bottom and typical river valley hillside.

Tapping Calendar: Taps placed just after January 1st.

Research shows that walnuts can be tapped at any time from late autumn to early spring, but we found the best time to tap is after January 1st--a week out from the first rise into above-freezing temperatures. And there's no harm in tapping trees ahead of time to avoid missing the flow of sap.

Drill Depth: 2 inches.

Tap and Collection Type: 5/16" Stainless steel micro taps with matching stainless steel hangers and 3 gallon sap bags.

The micro taps allow for more taps per tree while also doing less damage. The stainless steel, while costly on the front end, allows us to efficiently clean and store the equipment post harvest and we expect to provide us multiple years of use. We use the bags rather than buckets or hose lines and vacuum pumps because a majority of our trees are on a flood plain that will get water every year. Using bags reduces the cost of cleanup (or total loss) if the river floods its banks. Conversely, using bags increases employee work time as each bag needs to be collected separately once filled or in time to avoid fermenting in warmer temperatures.

Collection Method: By hand; all bags on trees are emptied into five gallon buckets that are, in turn, emptied into a 30-50 gallon open drum head style barrel (with clamped lid). The barrels are transported by a 2-person bench style ATV with back bed. Those barrels are emptied into 50 gallon storage barrels located by the evaporator.

Because we are a working farm that is diversified, we choose evaporating days by temperature. We do not have enough storage space for sap if temperatures go above 40F so we evaporate before sap spoils (souring as it goes into fermentation).

Evaporation Method: Sap is transferred from storage barrels to preheat on the evaporator via a five gallon bucket. The sap is cleaned by pour through a stainless steel 2 micron sieve. Sap is reduced as per maple sap using a hobby sized evaporator with three channels and draw-offs on either side. Sap was pulled at about 45 Brix (we just judge by a light amber color to the sap and heavier sweet flavor) to finish.

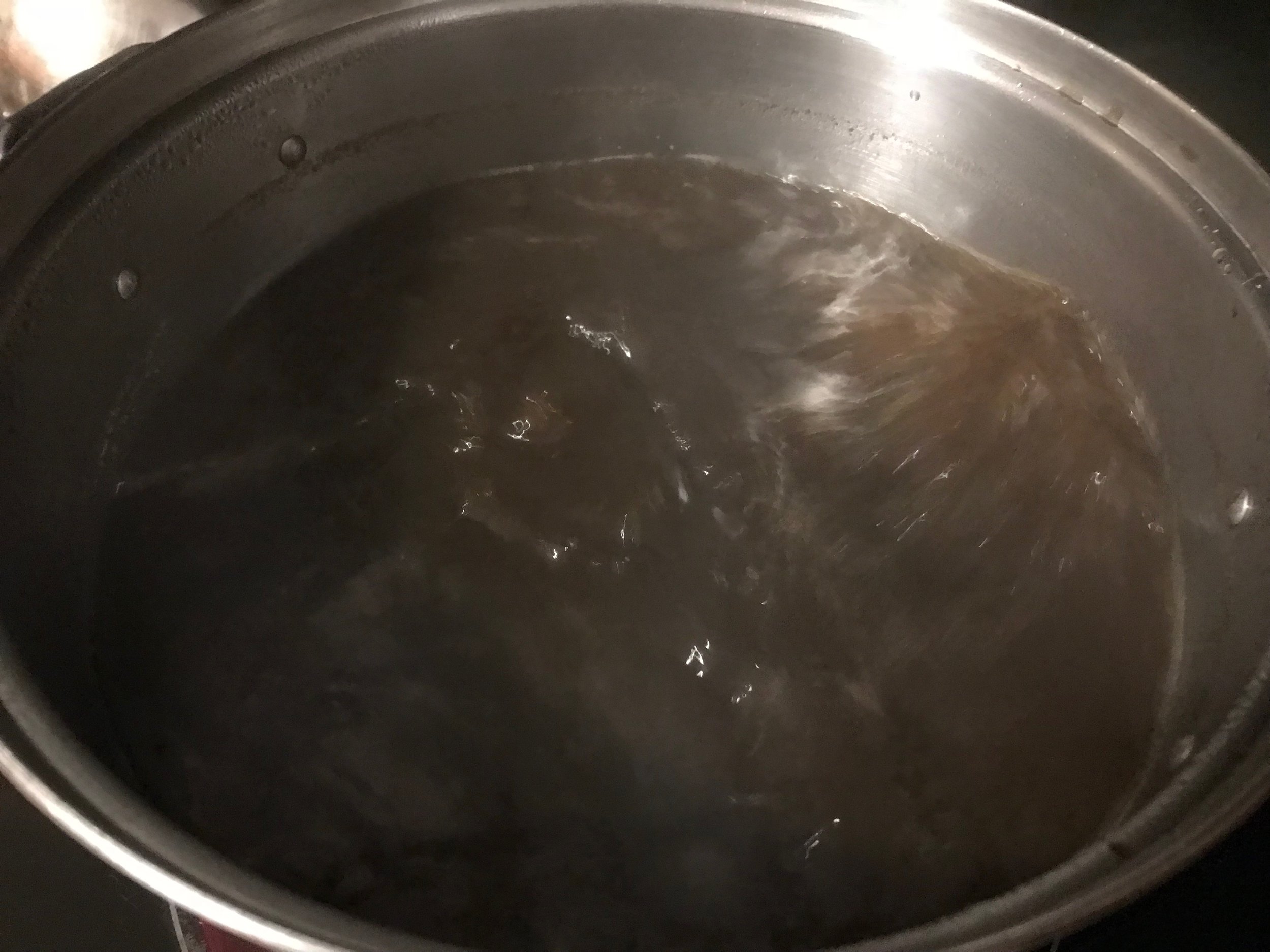

Finishing Method: Finishing is done on a stove or propane burner (identical to a fryer set-up). Sap is brought to a roiling boil and then immediately run through a standard cone filter to remove pectin. Sap is then returned to finish boiling until temperature reaches 220F. Bottle when done. The process with the exception of the pectin is identical to maple syrup production and the product quality in terms of flavor is outstanding. Final coloring is a deep amber to nearly black even if it is "thin."

This process will remove 90% of the pectin which will remain in the filter as a dark gelatinous brown goo. This substance MAY be known as "Walnut Jelly." We plan on doing more research as to its past historical use and the possible current day culinary uses.

The process--with the exception of the pectin elimination--is identical to maple syrup production and the product quality in terms of flavor is outstanding. Final coloring is a deep amber to nearly black even if it is "thin."

Additional Notes:

Side of tree to tap: Sun facing. Southerly and Westerly appear to produce most, with the south-facing to be most ideal.

Taps per tree: 1 per 12" diameter, but we think you can push it to as many as 1 per 10".

Minimum Tree Diameter: 8"

Per Tree Production: Varies widely. Overall production across the board to be about a gallon per tap per two day warm/freeze cycle. Some trees may produce a very small amount during that period of time while others produce three and even four gallons. Size of the tree has no bearing.

Sap-to-SyrupYield: Varies as well. The first batches of the season seem to match Sugar Maples with a 40:1 to 50:1 ratio of sap to syrup. That appears to increase as the season moves on or the taps are on the tree longer. At the close of the season when you are thinking about pulling taps off, that ration may be closer to a 60:1 ratio.